|

| Moorhen chick (Gallinula chloropus) |

...and the living is easy as difficult as ever!

With just a few days of sunshine in the bank, the longest day passed

by with little fanfare. It seemed as though the chance of summer was once again lost, and the meandering road through ever shortening days would lead us straight through to autumn. Then July arrived and the sun shone as the halcyon days of everyone's childhood.

It transpired that the two juvenile moorhen, previously sighted living around Baboon Island with their attendant parents, had no other surviving siblings. Maybe they never had. Through July, the population would decrease by half, as an adult and one of the chicks would also disappear.

On the river, three goosander ducklings kept close to their mother. Upon sight of me, two shuffled onto her back, while the third paddled behind, desperate to keep up. The British Trust of Ornithology (BTO) suggests that goosanders lay between 8 to 11 eggs, so three young ducklings with a long way to go before adulthood, doesn't appear to be much of a return. Being so young and small, they are particularly vulnerable to predators.

|

| Goosander (Mergus merganser) |

Further up the river, some older juveniles were congregated on the riverside rocks. They appeared much closer to adulthood, and had likely outgrown many of the predators capable of eating smaller prey.

Goosander (Mergus merganser)

Another water bird, the coot, was also seen caring for its chick. Slightly larger than the moorhen, the coot is easily distinguished by its striking white forehead and bill. Out of the water, its legs and feet are quite a sight. Being blue and somewhat disproportionate to the body, the feet appear somewhat clownish in their stride.

|

| Coot (Fulica atra) |

While the adults are distinctly black, the juveniles are fluffy and grey. The BTO reports that coots are aggressive birds that have been known to kill their own young, particularly if food is scarce. At such times it is the youngest, or smallest, to be chosen. On this occasion, there was only one juvenile whereas a coot usually lays between 5 to 7 eggs.

Juvenile coot (Fulica atra)

Cormorants are a common bird in this part of South Wales, and are often seen with their wings spread open to dry. As well as their regular appearances along the river, they are often spotted on the top of tall lampposts, looking like ornamental statues.

Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo)

There are concerns amongst fishery owners and patrons that the rise in the cormorant population is having an adverse affect on their fish stocks. Being far more skilled and adept at catching fish, the cormorant's influence on their sport is deemed to be so negative that those incapable of competing with the birds success have called for a cull. All birds are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, a bill that these sportsmen and women want amended. Personally, I do not agree with a sport that inflicts violence on another species. However, as someone who enjoys sport in general, I cannot help but conclude that such sports-people have failed to appreciate the true concept of sport. Apart from a cull being a direct contradiction of sporting behaviour, a sports-person's aim should be to change, adapt and improve their own performance to overcome obstacles, not simply remove those obstacles to make life and achievement easier. If your chosen sport is a competition against nature, than you should compete against all aspects of nature, otherwise you are simply removing the hurdles from a race.

Having only ever seen the common sandpiper on the coast, I was delighted to see this little bird on the River Tawe. Many sandpipers are summer visitors to the UK, and will migrate to warmer winters in Africa, although there are records of small winter populations in the UK. From a distance, I confused this sandpiper for a wagtail, such is the similarity of their almost constant teetering motion, which sees them bobbing up and down as they scour the water's edge for insects.

Common sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos)

One of the most unexpected and enjoyable sights of the summer was a lapwing strolling through the grass. What initially appeared as a black and white bird, suddenly took on the iridescent shine of sunlit oil. About the size of a pigeon, it has a distinctive crest, pink legs, and orange undertail coverts.

Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus)

Having stumbled across the lapwing, it looked at me for a moment as if assessing my intentions, before taking to the air. Due to a significant decline in the lapwing population, it has been identified as a red list species, requiring the highest conservation priority.

Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus)

The starling is another bird that has been granted red status. Given their serious decline, it was nice to see a new generation living on the Sanctuary's grounds. Unlike like the familiar shimmering colours of the adult, the juvenile starlings are a fluffy brown.

Juvenile starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

With the heat increasing across the ageing summer, this juvenile chiffchaff was making the most of the dry dirt, and was taking a dustbath on the track.

Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita)

The chiffchaff was one of many species spotted in and around the sanctuary this summer, that had not previously been recorded in this blog. Another species, the reed bunting, is a year-long resident that can be seen on farm and wetlands. A feeder of insects and seeds, it was moved from red to amber status in the list of priority conversation species. Following a significant decline in numbers, the reed bunting has made something of a recovery since 2009.

Reed Bunting (Emberiza schoeniclus)

The lesser redpoll and linnet are both birds listed red on the scale of conservation concern. Numbers of both species are in decline, which reflects their occasional sighting in and around the sanctuary.

Redpoll (Carduelis cabaret)

Linnet (Carduelis cannabina)

The whitethroat is another summer visitor that winters in sub-Sahara Africa. Similar in size to the resident great tit, its name reflects the white feathered throat. The male has a grey head and back while the female is a warmer brown. It is an amber status species.

Female whitethroat (Sylvia communis)

Male whitethroat (Sylvia communis)

Two birds that can be confused are the greenfinch and the siskin. Both are finches, dominated with shades of yellow and green, though the siskin is the smaller of the two species. In my humble experience, the greenfinch has been the more likely visitor to the garden. While neither bird is presently at risk, the RSPB reports a recent decline in greenfinch numbers, a result of an outbreak of trichomonosis, "A prasite-induced disease which prevents the birds from feeding properly".

Greenfinch (Carduelis chloris)

Siskin (Carduelis spinus)

The black headed gull is another frequent visitor to the sanctuary. Seen here in their summer caps, their heads will turn white in time for the colder weather.

Black headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus)

Certainly not a portrait piece, but this quick-fired snap caught the second of two kingfishers that darted out from the Nant Llech - behind the sanctuary - and onto the River Tawe. There were signs that the kingfishers were nesting in the banks along the Nant Llech.

Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis)

The introduction of Baboon Island a few years ago has provided a rich environment for all sorts of aquatic invertebrate.

Additional work at the Sanctuary has further enhanced the habitat, and multiplied the wildlife on view. By the time August arrived, several species of dragonfly and damselfly were living around the island, protecting territories, mating, and laying eggs. With the insect-life thriving, more and more birds were swooping to feast.

Common darter dragonfly (Sympetrum striolatum)

Golden ringed dragonfly (Cordulegaster boltonii)

Emperor dragonfly (Anax imperator)

Male broad-bodied chaser (Libellula depressa)

Female broad-bodied chaser (Libellula depressa)

A couple of broad-bodied chasers (Libellula depressa)

Large red damselfly (Pyrrhosoma mynphula)

Azure damselfly (Coenagrion puella)

Male common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum)

Female common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum)

Beautiful demoiselle (Calopteryx virgo)

As the dragonflies are drawn to the water, the butterflies are attracted to the vibrant, native wild-flowers allowed to grow naturally around the Sanctuary. Several different species of butterfly reflect the healthy population of plants.

The Whites

There are a few species of white butterfly, some of which are prevalent at the Sanctuary, and can be seen fluttering from flower to flower. The differences can be slight, and it is as they land to unfurl their proboscis and drink in the nectar that a definite identification is possible.

Green veined white butterfly (Pieris napi)

Small white butterfly (Pieris rapae)

Small white butterfly (Pieris rapae)

Large white butterfly (Pieris brassicae)

Brimstone (Gonepteryx rhamni)

Common blue (Polyommatus icarus)

Speckled wood (Pararge aegeria)

Ringlet (Aphantopus hyperantus)

Meadow brown (Maniola jurtina)

Small heath (Coenonympha pamphilus)

Small copper (Lycaena phlaeas)

Gatekeeper (Pyronia tithonus)

Red admiral (Vanessa atalanta)

Peacock (Inachis io)

Small tortoiseshell butterfly (Aglais urticae)

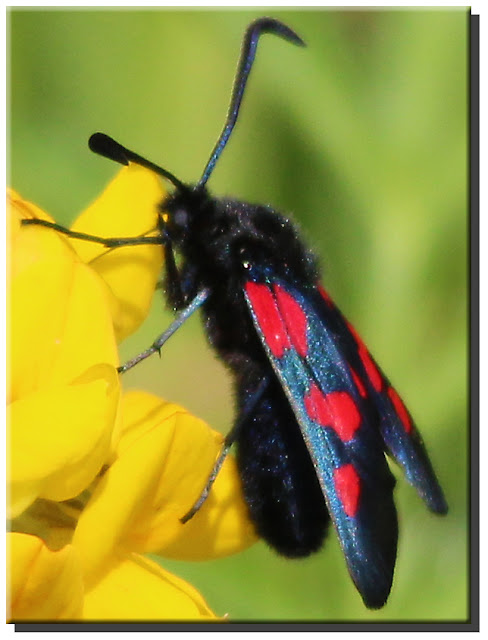

Cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae)

Cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae)

I have previously seen the cinnabar moth caterpillar at the Sanctuary, chewing its way through a ragwort plant. Where there is one there are usually dozens, distinctively dressed in yellow and black hoops. By the time September arrives, they are ready to pupate in preparation for the moth's arrival the following May.

Summer is closing down for the year, but it has provided the warmth we crave and nature requires. Those migratory birds that remain will soon chase the summer southward, leaving us to the trials of an unpredictable winter. But for now, at least, the sun continues to shine, allowing us to revel in the dying embers of a successful summer.

+female+01b.jpg)

+Male+01b.jpg)

+ispot+01b.jpg)